Conservatism and the Search for Moral Clarity

By Nathan Kahana

Many conservatives see Ivy League colleges as echo-chambers where left-wing ideas are treated as dogma. The solution, they claim, is to reinvigorate freedom of discourse: to give free reign to conservative voices so that colleges once again become sanctuaries of open inquiry. In this view, freedom of discourse is seen as a value we should aspire to.

But freedom of discourse is only valuable as a means to achieve moral clarity: an understanding of right and wrong that derives from an individual’s self reflection. While moral clarity is not truth in an objective sense, its attainment requires an attempt to arrive at the truth, motivated by the genuine desire to understand the difference between right and wrong. It is because this clarity is so rare that we often leave it unstated; many claim to know the difference between right and wrong, but in few cases does that “knowledge” result from a genuine search for truth.

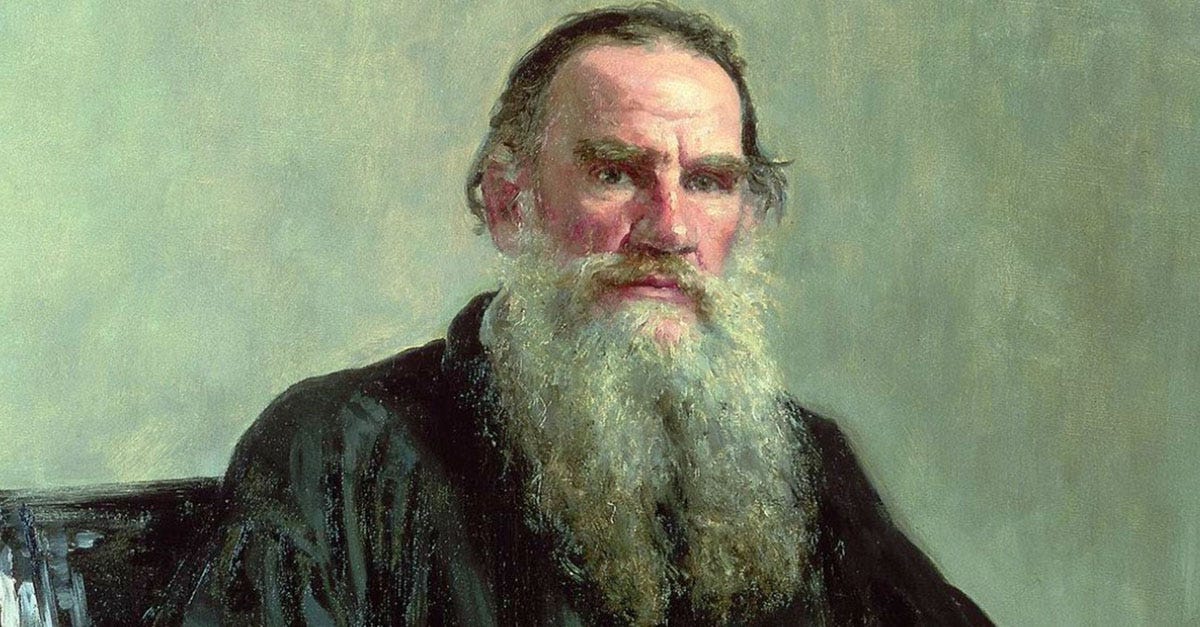

Reading Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy gave me an appreciation for the value of moral clarity. While many focus on its tragic depiction of an adulteress, I fixated on Levin, a Russian landowner with autobiographical origins. Levin begins the novel in a state of spiritual homelessness; he cannot join the nobility in their embrace of enlightened Western European values, but neither can he accept the dogmas that the Orthodox Church insists he embrace. One might expect that, lacking the stabilizing force of a community or the intellectual support from clear dogma, Levin would revert into moral apathy. Instead, he retains the conviction that moral clarity exists and is worth pursuing. The search he undertakes is not a public search, but a private one; the objective he aspires to is not a morality he can enforce on others, but one he can apply to himself. Moreover, while Levin attempts to find clarity in the works of philosophers, his search culminates not in a conclusion drawn from clear premises, but in a moment of intuition.

The goal of a conservative publication should be to facilitate our readers’ own search for moral clarity. There are three implications which follow from this objective. First, it should not lay claim to moral truths that require an uncritical acceptance of abstract dogma. Such dogma, regardless of the societal influence it may have had, deserves careful scrutiny. Second, it should acknowledge that this scrutiny must coexist with the recognition that moral clarity exists and can be attained by any individual, regardless of their background or prior knowledge. Finally, it should recognize that the search for moral clarity is not only one of many equally valuable goals that we desire to attain; it is the principal goal of our lives, one that we must direct all our attention towards.

The conservatism of such an institution should not constitute a predetermined course of action, nor an ulterior political motive, but rather a sympathy with the first principles that underlie conservative thought. Such principles include first and foremost the recognition that moral clarity is not merely an abstract term that can be undermined by critique, but a state of mind that must govern the life of every individual. In today’s world, conservatism is the only political viewpoint that consistently acknowledges the existence of moral clarity, even if some who profess it treat such clarity merely as a weapon.

We must undertake the search for moral clarity because the academy has forgotten the importance of that search. Instead, it often uses scholarly conventions to shroud a false and unquestioned moral consensus. The academy rarely entertains questions about that consensus; more often than not, it dismisses such questions as trivial and irrelevant. Only by revisiting these questions can we spark the state of wonder from which truth derives; only by revitalizing the search for moral clarity can we return Harvard to the stature it once held.

Well, this is a well written and pleasantly contemplative piece describing, I assume, the general purpose of the Harvard Salient, in its new incarnation. It touches on important, albeit somewhat abstract philosophical concepts. I will remain interested to see what comes next from this minority publication at Harvard.

When it comes to impact on the Harvard Community, however, the writers at the Salient will have to do more than wander in a field of daisies contemplating the morality of the philosophers on a sunny summer afternoon, as this piece seems to do.

To impact the world, or even just the Harvard Community, requires a much more significant journalistic effort. Fox News, for example, has succeeded in influencing the world towards more conservative ideas, and it's news coverage is decidedly less contemplative and more practical, not to mention more voluminous than the Harvard Salient.

If this meandering piece somehow helps to lead some deep thinkers in the Harvard Community towards more conservative thinking, that is to the good, but it strikes me as too ethereal to have much impact. In my experience, deep thought is better applied to the physical, chemical, and biological sciences where it can be put to more practical use than it can in politics and philosophy. In retrospect, that is why I chose, back in 1985, to concentrate in Biology as opposed to my other option, which was Government.

In any event, I do applaud the small conservative gains made recently at Harvard, including certain changes in the faculty. Of particular note, I wholeheartedly endorse President Garber's statements about Harvard being an institution of education, not activism. The development of the young mind is better served by objective teaching of all sides of an issue, followed by an opportunity for students to come to their own conclusion(s) and to express them without fear of retribution from activist professors.

Indeed, a highly activist faculty turns Harvard into an institution of indoctrination rather than an institution of education. The faculty activism and intimidation must end, and perhaps this would be a somewhat more tangible and practical issue for the Salient to focus on.

Jonathan L. Gal

AB Biology '89

This philosophical babble has caused me to yearn for the previous, and much more relevant Salient. Bring back the former editors, this mealy-mouthed stuff is painfully boring and ineffectual. Booooooo……