Martyrs Without a Cause: Students Mourned the Dead but Can Not Say What They Died For

By Charlotte T. Nakhla

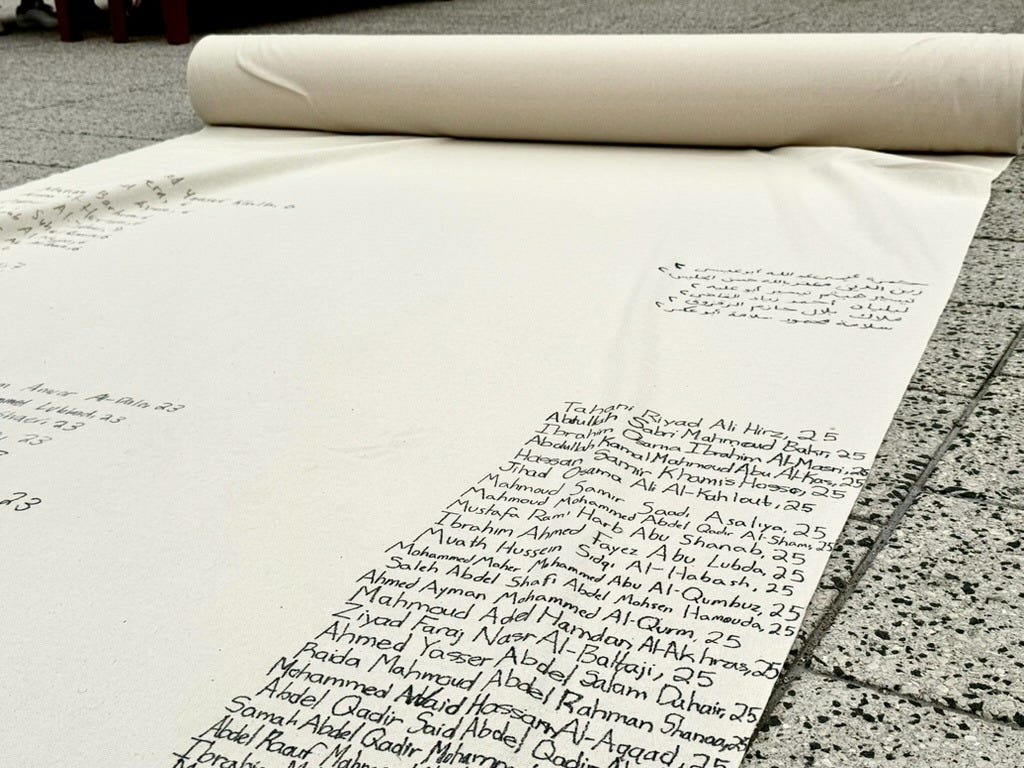

On the morning of October 11th, three or four people kneeled around a long white banner in Harvard’s Science Center Plaza, writing names—hundreds of them. Each belonged to a Palestinian said to have been killed since the start of the war.

Next to every name was an age. The numbers 12, 4, and 0 appeared often. Thousands of children were born into this mess; it is undeniably tragic. But another pattern emerged too—men in their twenties. I will return to that.

The name-writing was organized by the Palestine Solidarity Committee (PSC) and lasted four days, from October 8th through the 11th, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. each day (save for a rainy Wednesday morning). On Thursday night, the group held a vigil before Memorial Church in memory of October 7th. According to The Harvard Crimson, they played a twelve-minute recording listing the earliest people killed—or, as they called them, martyrs.

Why martyrs and not victims? Martyrs die for a cause: for Palestinian statehood, anti-imperialism, “liberation.” But which cause exactly?

I asked two of the people writing on the banner. Neither seemed sure.

One, a student, said it was about “reframing”—a way to highlight that the Palestinians “died for freedom.” The other, an administrator, thought it might be a religious thing, though she admitted she wasn’t that familiar with Islam.

I sat down to talk with her. We agreed that we wanted the bloodshed to stop. I asked where she had gotten the list of names. She wasn’t sure. She said she was shaky on the conflict’s history, on the region itself, and that she was disturbed by Islamist regimes. I respected her honesty—but I could not help thinking: then what are you doing here?

She told me one thing she did know: that the Palestinians have been deprived of their land for decades, so in that context, “resistance” is understandable.

That word—resistance—deserves scrutiny. In the Gaza Health Ministry’s official statements, every Palestinian killed is called a martyr. The term isn’t selective; it includes the attackers who died on October 7th. In Islamic teaching, those who die in battle are promised paradise—the first among martyrs. But the woman I spoke with didn’t know that. How could she?

Forget, for a moment, the theology. What, exactly, does a “Free Palestine” look like? How does one deradicalize entire generations steeped in hatred? How should Israel have responded to the attack? What of the Israeli political factions that wish to annex Gaza? What about the foreign governments funding and arming Hamas? And how do we trust any of the “information” emerging from the war at all?

If the PSC can answer these questions, I’d be impressed. I cannot. Generations of world leaders have not.

So what are they doing here? What do they think their protests and encampments accomplish? If you don’t understand what a situation is, you cannot possibly know what should be done. That’s how incoherencies like “Queers for Palestine” emerge. It’s how, over the last month, some have come to believe that cold-blooded murder can serve the greater good.

It’s a mistake to believe that campus activism is primarily driven by meticulously planned “subvertion” or even mal-intent. Many students have this instinct for charity, a need to help, and they aim it towards whatever cause seems good at the moment (after all, my friends can’t all be wrong, right?). But good instincts must be directed by understanding. Otherwise, activism becomes irresponsibility—and, ultimately, futility. The PSC’s efforts did not affect the war in Gaza. Beyond a few sympathetic headlines, they achieved nothing at all.

So, as the fight in Gaza winds down for now, I expect it won’t be long before they jump onto the next shiny cause. One hopes that, before they kneel again to write names they do not understand, they pause to ask a simple question:

What am I doing here—and what am I doing it for?

It should also be noted that there are some (many) paid protesters at these kinds of events. They do it, quite simply, for the paycheck.