The Empty Promise of American Higher Education

On Harvard's Refusal to Comply with the Federal Government

On April 14th, President Garber announced that Harvard would not comply with the federal government’s demands to reduce anti-Semitism on campus, improve ideological diversity, and end DEI initiatives. In response, the federal government paused over two billion dollars of research grants and other funding to the school. Commentators have been quick to label this an attack on Harvard, and the Crimson Editorial Board, for instance, called Garber’s letter “courageous” and “noble.” This perspective is shortsighted. It is out of love for Harvard that I welcome the Trump Administration’s efforts to restore her standards and end the distractions that pervade campus life. I do not believe the university administration is capable of or interested in making Harvard the kind of institution that she ought to be, yet she is too important for America to simply let her go.

It is clear that Harvard is in need of a serious course correction. It is manifestly unacceptable that a small group of students went basically unpunished after seizing a campus common area to propagate anti-American ideals. It is untenable for our professors and administrators to be so ideologically uniform that the duty falls to a small minority of students to ensure that our peers are aware of alternative worldviews. It is divisive for Harvard to use race to define the student experience, both formerly as a qualification for admission and still as the focus of a great many affinity programs. It is embarrassing that we had to create a new remedial math course this year because our admissions criteria are so twisted that we failed to make sure prospective students knew basic algebra. Is this the Harvard we were promised?

Fortunately, the government has provided a vision for a revitalized Harvard that can begin to address these issues. The government’s plan will first remediate the proximate cause of this effort: widespread anti-Semitic and anti-American campus activism. The government’s plan would prevent university programs from promoting such views, and students would be punished for harassing others or breaking university rules. The government’s effort also focuses on restoring meritocracy and viewpoint diversity on campus—all noble goals for a noble university.

The government’s treatment of the university’s hiring practices gives a good picture of how it wants to achieve these goals. The government’s proposal would have required the university to get rid of preferential hiring based on factors such as race, sex, or religion by August of this year. These preferences have little relation to one’s competency to teach, research, and write, and getting rid of them is a natural extension of the same movement toward meritocracy that the university was forced to undergo when affirmative action in admissions was prohibited. The proposal would also have required the university to review both existing and proposed faculty for plagiarism, a policy which, before the Claudine Gay scandal, I assumed the university did as a matter of course. Avoiding similar scandals in the future, as well as our general interest in ensuring that faculty are actually qualified, clearly justifies such a measure.

Perhaps the most controversial part of the proposal is the requirement that each academic department has viewpoint diversity. Part of that effort—the elimination of ideological litmus tests, implicit or explicit—is clearly necessary to that end and is justified by that same general interest in not disqualifying well-equipped teachers for extraneous reasons. The plan would also require Harvard to “hir[e] a critical mass of new faculty within [each] department or field who will provide viewpoint diversity.” Obviously, the details are important here; which viewpoints exactly must be represented would, no doubt, have been a major point of contention between the university and the government. If we assume that it refers first and foremost to the representation of conservative ideas, however, the case becomes clear. As Professor Mansfield argued last month, “Harvard needs conservative faculty to improve the quality of what is commonly heard and thought, to expand the range of its moral and political opinion, and to help restore demanding academic standards of grading.” To take just the first of those points, Harvard students will be unprepared for modern political life, and thereby leadership in contemporary society, if they are unfamiliar with the ideas and beliefs motivating the modern Right. Leftist instructors can teach those ideas in an unbiased way—just as right-wing teachers can teach Marx—but, in my experience, they have very little appetite for doing so.

But Harvard’s defenders seem less interested in the merits of the proposed changes than in the purported powers of the federal government. In his letter, President Garber stated that “the University will not surrender its independence or relinquish its constitutional rights.” Of course, as my successors on the board of the Harvard Republican Club have already noted, “it is not the constitutional right of any private university to receive federal funding in perpetuity.” These appeals to legality hide that the university has a choice in the matter: be a public institution responsive to the public will, or accept the financial realities that come with being a truly private institution. I am sympathetic to the idea that this move will establish an undesirable precedent for future progressive administrations to pressure universities in the opposite direction. But unless Congress somehow permanently withdraws from the executive its broad discretionary powers to set terms for the distribution of federal grants, we conservatives should not unilaterally disarm ourselves. The Leviathan does not ask our permission before it lurches left.

The government’s terms only sound shocking when we ignore the Left’s decades-long exercise of government power against universities. Indeed, Americans have long accepted that universities do not have total autonomy so long as they accept federal money. Bob Jones University, a private religious university, rightfully had its tax-exempt status revoked in Bob Jones University v. United States after refusing to integrate its student body. More recently, the Obama Administration used a “Dear Colleague” letter from the Department of Education in 2011 to force every university receiving federal funding to adopt standards for reviewing sexual assault allegations that left the accused with far fewer protections than in a court of law.1 Nor is this close connection between the government and the daily governance of the university new to Harvard. Our first president, Henry Dunster, resigned after the General Court of Massachusetts bristled at his theological heterodoxy.2 Whether individual cases, like that “Dear Colleague” letter, were imprudent is debatable. What is important, however, is that only now have we decided this sort of action is ipso facto illegitimate. Indeed, it is Harvard’s acquiescence to previous instances of government policy that makes its sanctimonious defense of academic liberty today ring so hollow. There is no doubt that, were the federal government to make progressive demands of the University, she would fall in line, as she has long done. Whether these specific measures will stand up to constitutional scrutiny is a matter for the courts to decide, but the general principle of government oversight of publicly funded universities is well-established.

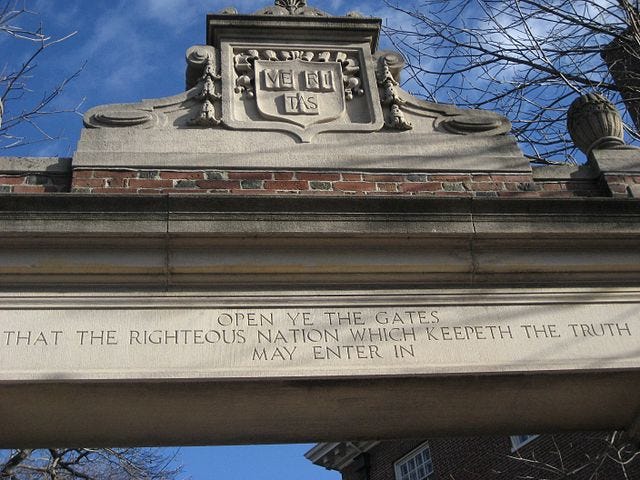

Furthermore, while Harvard has a choice in the matter, it is not an act of heroism for the University to disentangle itself from the government. Some universities, seeking nothing more than to be factories for the generation of knowledge, may be content to pursue their studies without reference to the outside world. Others, particularly religious institutions, may ground themselves in ideals even higher than the public interest (though our own history demonstrates that even those two goals need not be in conflict). But our pursuit of Veritas has always been furthered by deep connections to the society we serve. As the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 affirmed, “Wisdom, and knowledge, as well as virtue, diffused generally among the body of the people, being necessary for the preservation of their rights and liberties… it shall be the duty of legislatures and magistrates, in all future periods of this commonwealth, to cherish the interests of literature and the sciences, and all seminaries of them…” This description doesn’t govern the legal relationships between Harvard and the federal government, but it informs our sense of purpose. President Garber was right to note with pride that Harvard’s ties to the government have historically amplified its ability to serve the nation. In light of the university’s failures, however, he is wrong to suggest that the government has broken those bonds. Within constitutional bounds, it is the government’s duty to help correct universities—especially ours—when they stop serving the public good.

While Harvard’s mission has evolved over the years, it is no less public-minded than it was in 1636. It is summed up in the declaration of the College that she will “educate the citizens and citizen-leaders for our society.” It is hubris to assume that one can lead a society while walling oneself off from the majority’s judgment. Americans are tired of seeing mobs form in the Yard. Even more than that, we are tired of being governed by a self-righteous elite blinded by ideology. The American people should not foot the bill while our preeminent institution of higher education drifts away into nonsensical progressive activism. To do otherwise would be to allow the rot to fester. That, not the Trump Administration’s shock therapy, would be the true act of disloyalty to our alma mater.

Campus Sexual Assault: Obama Administration Harmed Survivors | National Review

Specifically, after he repeatedly announced his support for credobaptism, the General Court passed a resolution encouraging the Overseers of the College to take special care that its instructors be sound in the Christian faith. Wood-winter-2005-combined.pdf

John Lonergan, HBS '76: Alexander Hughes’ article brilliantly exposes the urgent need for Harvard to realign with its public mission and shed the ideological shackles that undermine its legacy. I wholeheartedly support his call for reform, as Harvard’s current trajectory risks eroding its role as a beacon of merit and intellectual diversity. The article rightly critiques the university’s resistance to federal oversight, which could address critical flaws in its admissions and culture. Harvard’s main faults lie in: (1) its unwillingness to accept students with non-progressive political views, stifling the viewpoint diversity essential for robust discourse; (2) hidden discrimination against high-achievers, including Asians, as evidenced by ongoing lawsuits and admissions data, which betrays the meritocracy Hughes champions; and (3) a focus on "exclusivity," akin to luxury brands like Rolex or Ferrari, rather than expanding class sizes to educate more leaders. If Harvard truly adds value to society, as its mission claims, why not dramatically increase the number of students it educates, amplifying its impact? The government’s push for accountability, as Hughes argues, is not an attack but a lifeline to restore Harvard’s commitment to Veritas and public good. By embracing these reforms, Harvard can reclaim its role as a forge for citizen-leaders, not a cloistered elite.

Yes, Harvard had it coming, as do Princeton, Yale, Columbia and down the line… Achieving a diversity of viewpoints on the faculty is going to be extremely difficult as existing faculty regularly vote down candidates whose work is perceived as “Eurocentric,” “conservative,” or who have, perhaps, ventured to criticize aspects of critical race theory.