The Golden Calf of Process

A guest post by Kimo Gandall

“In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did what was right in his own eyes.” - Judges 17:6

This spring, the Harvard Federalist Society added a basic tie-breaker rule: if Robert’s Rules of Order and the Society’s Elections Code failed to resolve a deadlock, the elections chair would appeal to natural law first principles to decide the controversy.

Cue Sarah Isgur, JD ’08—“conservative commentator,” anti-Trump Republican, and co-host of a podcast with David French, JD ’94. She mocked this otherwise modest rule change on air, scoffing that using natural law as a tie-breaker meant “correct outcomes… are more important than process.”1 To underscore her point, Isgur read aloud a quote from Professor Adrian Vermeule ’90, JD ’93: “The common good condemns the abuse of official power for private purposes like nepotism or peculation; it underwrites equitable and public-regarding interpretations of semantic and legal meaning; and it helps to prevent a kind of pointless and fetishistic legal formalism that benefits few and harms all.”2

Ignoring Isgur’s odd preoccupation with the sexual lives of law students,3 we can, for the sake of Catholic charity, admit that it is true that many sincere conservatives believe method is what keeps power honest. To invoke natural law, they likewise argue, is to announce that substance swallows structure and someone’s morality will rule the rest of us.4

This little campus skirmish exposes a much larger fault line on the American Right over whether the legitimacy of law lies primarily in the procedures that generate it or in the ends it serves. Christ’s condemnation is simple: “You leave the commandment of God, and hold fast the tradition of men.”5 In other words, “Si principi placet quod lex nature non habeat locum in suis actis, tale beneplacitum non est lex,” or “If the Prince decrees that natural law has no place in his enactments, such a decree is not law.”6

Modern American conservatism was forged in the courts as much as at the ballot box. From the Warren Court backlash to the Reagan Revolution, its unifying professional ambition has been the restoration of process: the separation of powers, textual fidelity, majoritarian rulemaking.7 The achievement is real—few law students finish a first-year course on legislation and regulation without hearing the hymn of Justice Gorsuch, JD ’91, that only the “written word is the law.”8 Yet, devotion can curdle into idolatry. When method becomes its own moral horizon, conservatives risk treating the mechanics of self-government as an ultimate good rather than a means ordered to higher goods.

Benjamin Pontz ’24, the prior President of the Harvard Federalist Society, embodies this impulse with almost perfect candor: “…the idea that self-government according to a rule of law prescribed in advance through methods that are ours until we change them has inherent value, independent of particular outcomes.”9

Compare this to St. Thomas Aquinas’s sober instruction: “Since the law is chiefly ordained to the common good, any other precept… must be devoid of the nature of a law, save in so far as it regards the common good.”10

The two sentences pull in opposite directions. Pontz treats lawful procedure as self-justifying; Aquinas treats procedure as an instrument whose worth rises and falls with its contribution to the common good. Too many contemporary conservatives—including Isgur, if she properly understands her own argument—have slipped into the Pontz position, or a sort of procedural fetishism, wherein the process itself is justified independent of any outcomes it may facilitate.

The Natural Law Antithesis

Without diving too deeply into the literature, readers should be familiar with two simple syllogisms provided by Aquinas, that cement the natural law ontology of law.

First, beings act towards an end. That is:

P1: Every action tends toward something determinate.

P2: What is determinate functions as an end relative to the action.

C: Therefore, every agent, by acting, intends some end.

Even non-intelligible beings, Aquinas argues, act towards some end. Plants, for example, grow and reproduce as part of their nature. Though Aquinas develops this point within a cosmological argument for God’s existence, it also has application to the law.

P1: If something is contingent, it is reasoned.

P2: Human actions are contingent.

P3: Law is a human action.

C: Therefore, law is reasoned.11

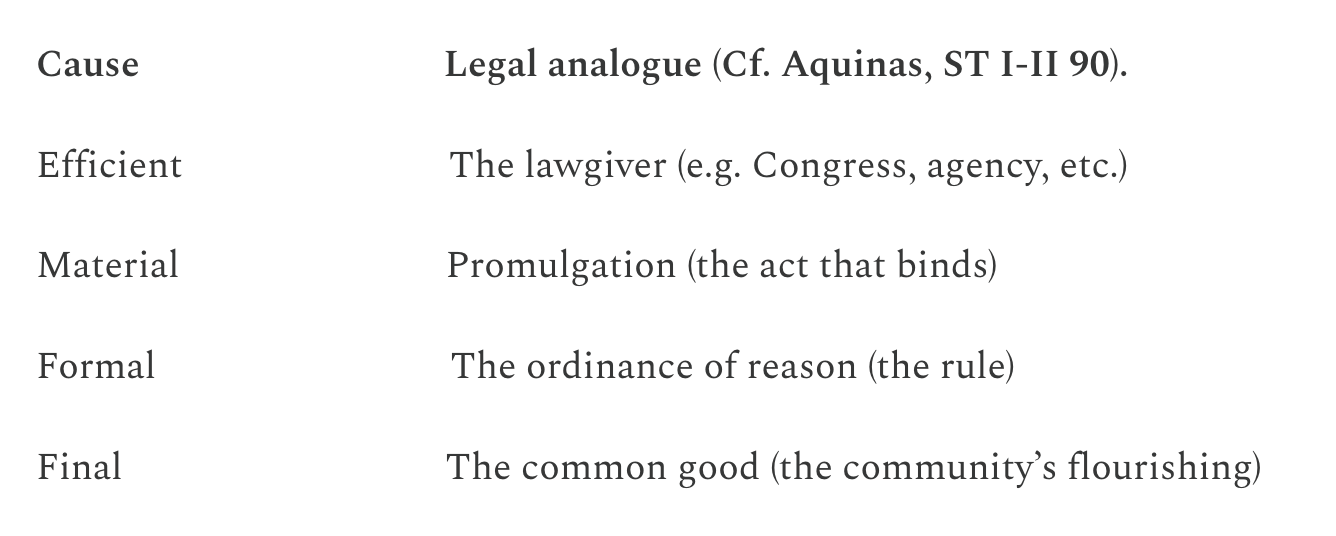

Moreover, human beings have purpose; that is, they are teleological creatures. We act for reasons and toward ends that perfect our shared nature. Law, defined as “an ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has care of the community, and promulgated,”12 likewise possesses four classical causes:

Strip away any cause and what remains is not fully lex. Natural-law jurisprudence therefore resists both pure voluntarism (the will of the sovereign is enough) and pure formalism (the words alone are enough). Text must be read in and through the background grammar of the common good, linked with promulgation, the lawgiver, and the ordinance of reason. That is, in the words of Vermeule: “[classical American] jurists did not explain the legality of moral principle by adverting to social facts, judicial choice, or more fundamental laws; on the contrary, they seemed to treat ‘moral laws’ as self-evident, unchangeable, and applicable ex proprio vigore [of their own force].”13

When method becomes its own moral horizon, conservatives risk treating the mechanics of self-government as an ultimate good rather than a means ordered to higher goods.

To recite perhaps a more familiar text, the Federalist Papers No. 57 instructs that “The aim of every political constitution is, or ought to be, first to obtain for rulers men who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue, the common good of the society; and in the next place, to take the most effectual precautions for keeping them virtuous whilst they continue to hold their public trust.”

Bostock is the Gnosticism of Process

Process worship and fetishtic textualism share the same roots in abstracting legal meanings and background principles from text. Justice Gorsuch’s Bostock provides an example of this textualism, one incidentally reflective of a neo-Gnostic gloss on Title VII. Gnosticism, ancient and modern, pries spirit from body; Bostock achieves the same divorce by disentangling statutory form from statutory telos.

In Bostock, the Court contemplated if the “ordinary public meaning of Title VII’s command that [it] is ‘unlawful… for an employer to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his… sex” means that Clayton County must retain a gay employee who handles children.14

Justice Gorsuch lifts the phrase “because of… sex” from its 1964 soil—where “sex” denotes embodied male-female complementarity ordered to family life—and treats it as a free-floating semantic cipher.15 Once the text is severed from its procreative purpose, the Court can announce, with the assurance of a mystery cult offering a ‘thought experiment,’ that firing a male employee for dating men is ipso facto “sex discrimination,” because one must mentally register his biological sex to perceive his orientation.16

To explain his argument, Justice Gorsuch provides the following thought experiment:

“Imagine an employer who has a policy of firing any employee known to be homosexual. The employer hosts an office holiday party and invites employees to bring their spouses. A model employee arrives and introduces a manager to Susan, the employee’s wife. Will that employee be fired? If the policy works as the employer intends, the answer depends entirely on whether the model employee is a man or a woman. To be sure, that employer’s ultimate goal might be to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. But to achieve that purpose the employer must, along the way, intentionally treat an employee worse based in part on that individual’s sex.”17

The following rebuttals between Justices Gorsuch and Alito go like this: Justice Alito responds that the same hypothetical can be applied to a series of checkboxes, wherein an applicant can check a box revealing homosexuality without revealing sex.18 Justice Gorsuch responds that, “even in this example, the individual applicant’s sex still weighs as a factor in the employer's decision.”19 At the core of Gorsuch’s reasoning is the removal of motivation as a necessary element of the law; he assumes that two individuals can be “materially identical in all respects, except that one is a man and the other a woman,” while both are homosexual.20

This maneuver is pure Gnosis: hidden insight (the counterfactual “but-for” test) overrides the plain, procreative nature of sexuality.21 Indeed, Justice Alito points out, albeit in a footnote, the obvious: a man and a man or a woman and a woman can never produce a child naturally.22 Applied to Aquinas’ formulation, Bostock divorces the final cause—what sex is orientated towards—with the formal cause. Justice Gorsuch’s assumption violates a basic tenant of the classical legal tradition, because it reads the reasoned ordinance of a legitimate authority—Congress—without any application to the common good; in effect, Justice Gorsuch denies that anti-discrimination statutes related to sex has any meaningful implication on “the flourishing of a well-ordered political community.”23 Again, a reading of the formal cause necessarily requires reason for the common good. In layman’s terms, speaking of sex without procreation divorces the teleological roots of Congress’s substantive legal command.

Consequently, for the fetishistic textualist, the formal cause triumphs the final cause, compelling Clayton County to hire a gay man handling children.24 The majority insists it is merely bowing to “the written word,” yet the word it venerates is a text de-incarnated, cut loose from Congress’ moral architecture and floated into abstraction.

Conservatives who long equated fidelity with textual purity now confront the grim epiphany St. Augustine saw in the Manicheans: a law stripped of its created order becomes a mechanism for un-creation. If the conservative legal movement cannot fuse text to telos, cannot insist that “sex” in law means what sex means in flesh, then Bostock will stand as the canonical heresy of our jurisprudence—a stunning proof that secret knowledge, when blessed by impeccable process, can demand that one believe a lie.

Retooling Conservative Jurisprudence

Of course, while Bostock is technically about reading text and not due process, its cautionary tale rings true in both worlds: legal meanings must be welded to the reality it serves. That is, conservatives must insist that ordinary meaning rationalizes ordinary metaphysics: a statute that uses “sex” or “mother” or “marriage” silently imports the bodily, procreative, familial goods those words name. Likewise, an election process designed to “enable the overall membership of an organization… to establish and empower an effective leadership” must be orientated towards that end.

In the context of the Harvard Federalist Society, that could mean—and very well should mean—that a future Election Chair is legally commanded to remove those candidates who engage in “The act of promoting, endorsing, or advocating for views, actions, or causes that are in direct conflict with the stated mission, values, or objectives of the organization, as outlined in the Harvard Federalist Society Constitution.”25 Those values, embodied in the background text of our country, could potentially implicate: Marxism, or any variation thereof; feminism, or any variation thereof; pro-abortion ideology, or any variation thereof; secularism, or any variation thereof; or opposition to the traditional, naturally-ordered family, or any variation thereof. It will be upon the future Election Chair to decide these issues, although a strong statutory command can be read for these, given the background literature in classical legal theory that provides meaning to the words that the “State exists to preserve freedom,” that the “separation of powers is central to the Constitution,” and that, “it is emphatically the province and duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be.”26 Doing so will require courage.

Text must be read in and through the background grammar of the common good, linked with promulgation, the lawgiver, and the ordinance of reason.

Justice Gorsuch, ironically, is correct that words have meaning. But future Election Chairs should understand that peeling away the signifier of substance licenses horrors—none clearer than Justice Alito’s Bostock dissent in footnote six to John Money, PhD ’52.27 Money, the psychiatrist lionized for coining “gender identity,” treated language as pure self-definition. His most famous experiment—that of the Reimer twins—tried to prove that “girl” could be grafted onto a boy’s mutilated body through surgical cosmetics and ritualized “female training,” which included forcing one twin to perform sexual acts on the other while Money photographed the sessions.28 The linguistic alchemy failed and David Reimer eventually took his own life. Yet the American Psychological Association doubled down, praising Money’s “seminal concepts” and exporting his terminology into every modern stylebook.29 That is how a dictionary emptied of metaphysical ballast becomes a delivery system for evil: the word “gender” floats free, replaced in flesh by a modern Sodom.

The Harvard Federalist Society’s election, and subsequent disputes over process, is emblematic of a struggle within the conservative intelligentsia—that is, whether process is a good within itself, or if process must be justified on substantive grounds. If the procedural conservatives win, we will follow a vision of the law like that of Justice Scalia, LLB ’60, where evil is technically good law, and our only remedy is to resign from government. To recite Justice Scalia on the Holocaust: “...if I were a judge in Nazi Germany, charged with sending Jews and Poles to their death, I would be obliged to resign my office.” In Justice Scalia’s vision, law is a nihilist endeavor—a jurisprudence of no rhyme or rhythm, but a mere amoral machine. If, however, substantive conservatives win, the classical legal tradition prevails, and we root law in the common good. That means, unlike Justice Scalia, we are not obliged to resign from an evil government perpetuating the Holocaust, but are called to actively subvert, undermine, and eventually seize, that government. Substantive conservatism is a living, not dead, theory of law.

Leftists and procedural conservatives alike will represent substantive conservatism as an “antiquated and parochial belief,”30 but they underestimate the memetic power of Biblical wisdom.31 In 2 Chronicles 34, we are told of the coming of King Josiah. King Josiah emerges from a period of social and cultural turmoil, as his father, Manasseh embraces paganism, dispossessing the Jewish people.32 King Josiah—before he was even twenty-one—embarked on a campaign to reclaim his nation from the Pagans:

In the eighth year of his reign, while he was still young, he began to seek the God of his father David. In his twelfth year he began to purge Judah and Jerusalem of high places, Asherah poles and idols. Under his direction the altars of the Baals were torn down; he cut to pieces the incense altars that were above them, and smashed the Asherah poles and the idols. These he broke to pieces and scattered over the graves of those who had sacrificed to them. He burned the bones of the priests on their altars, and so he purged Judah and Jerusalem.33

The substantive conservative—especially the conservative in positions of power, whether in the Joseph Story Society, the Federalist Society, the College Republicans, or elsewhere—can learn much from King Josiah and the natural law tradition; that is, to reclaim an idea of political imagination—what some have called history and tradition—and enact positive law that directs the polity to the common good.34 Our tradition not only teaches this, but demands it. Students of law should leave knowing the words literally engraved on the walls of Langdell Hall: Non sub homine, sed sub Deo et lege. That is, Not under man, but under God and law.35

Kimo Gandall, JD '25 was the 2025 Harvard Federalist Society Election Chair and Advisory Board Member. Gandall is currently CEO and founder of Fortuna-Insights, a legal technology company focused on automating the court system.

Sarah Isgur and David French, “Is Trump Going to War Against the Rule of Law?,” Advisory Opinions, at 1:30:46.

Ibid. at 1:29:16.

Ibid. at 1:36:42 (“they’re not performing well… many at the bottom of their class in grades… and they’re very, very single. And history is littered with the stories of young men who are frustrated and can’t get chicks.”).

Ibid. at 1:30:28.

Mark 7:8 RSVCE

Baldus de Ubaldis, commentary on Digest 1.4.1.

See Antonin Scalia & Bryan Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts, 24.

Bostock v. Clayton County, 140 S.Ct. 1731, 1737 (2020).

Compare Benjamin Pontz, “Review: Keeping our Republic,” Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, No. 40, 2 (2023) [emphasis added].

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiæ II-I, q. 90, a. 2 [emphasis added].

Ibid. a. 1 (“Now the rule and measure of human acts is the reason, which is the first principle of human acts… since it belongs to the reason to direct to the end, which is the first principle in all matters of action, according to the Philosopher (Phys. ii). Now that which is the principle in any genus, is the rule and measure of that genus: for instance, unity in the genus of numbers, and the first movement in the genus of movements. Consequently it follows that law is something pertaining to reason.”).

Ibid., a. 4.

Adrian Vermeule, “Enriching Legal Theory: Response to the Symposium on Common Good Constitutionalism,” Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2023, quoting Emad Atiq, “Legal Positivism and the Moral Origins of Legal Systems,” Canadian Journal of Law & Jurisprudence, 2022, 26.

Bostock, 140 S.Ct at 1739.

Compare Bostock, 140 S.Ct at 1742 with Bostock, 140 S.Ct at 1760 (Alito, J., dissenting).

Bostock, 140 S.Ct at 1742.

Ibid.

Ibid. at 1746.

Ibid.

Ibid. at 1761.

Ibid. at 1739.

See Bostock, 140 S.Ct. at 1837 n. 19 (Alito, J., dissenting) (“Notably, Title VII itself already suggests a line, which the Court ignores. The statute specifies that the terms ‘because of sex’ and ‘on the basis of sex’ cover certain conditions that are biologically tied to sex, namely, ‘pregnancy, childbirth, [and] related medical conditions.’ 42 U. S. C. §2000e(k). This definition should inform the meaning of ‘because of sex’ in Title VII more generally. Unlike pregnancy, neither sexual orientation nor gender identity is biologically linked to women or men.”). [emphasis added]

Vermeule, infra note 29, at 17.

Ibid. at 1737-1738.

Ibid. The Code I have cited in this paper does not technically extend into the next year, and should be promulgated immediately again at the beginning of the year. Of course, the future elections chair should consider prudential extensions of the positive law (i.e. the code) that might further facilitate these ends, of which were simply not politically practical for the initial code. These would include, for example, interviewing candidates to align them with the express purpose of the society, and eliminating those who demonstrate commitments contrary to the Federal Society’s values.

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, 131 (New Orleans: Quid Pro Books, 2013) (“The aim of every political constitution is, or ought to be, first, to obtain for rulers men, who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue, the common good of society; and, in the next place, to take the most effectual precautions for keeping them virtuous…”); Adrian Vermeule, Common Good Constitutionalism, 59 (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2022) (“In the classical theory, the ultimate genuinely common good of political life is the happiness or flourishing of the community, the well-ordered life in the polis”); Confucius, The Analects, trans. Simon Leys, 2.16 (“The Master said, ‘The gentleman [junzi] understands what is morally right. The petty man [xiaoren] understands what is profitable.’”); Justinian I, The Institutes of Justinian, trans. J.B. Moyle, 7 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913) (“The precepts of the law are these: to live honestly, to injure no one, and to give every man his due.”); 1 Timothy 2:11–12 RSVCE (“Let a woman learn in silence with all submissiveness. I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent.”).

See Bostock, 140 S.Ct. at 1837 n. 6.

Phil Gaetano, “David Reimer and John Money Gender Reassignment Controversy: The John/Joan Case,” Embryo Project Encyclopedia (Arizona State University) (September 11, 2023) (“Reimer and his twin brother were directed to inspect one another’s genitals and engage in behavior resembling sexual intercourse. Reimer claimed that much of Money’s treatment involved the forced reenactment of sexual positions and motions with his brother. In some exercises, the brothers rehearsed missionary positions with thrusting motions, which Money justified as the rehearsal of healthy childhood sexual exploration… at the age of thirty-eight, Reimer committed suicide by firearm.”); The irony of Money’s deep influence on the American Psychological Association (APA) is that his work—which the APA traces as early as the 1950s, with a strong emphasis on gender in the 1960s—may also provide originalist grounds for arguing that transgenderism falls under the APA definition (see Distinguished Scientific Award for the Applications of Psychology, infra note 32, citing John Money, “Effeminacy in Prepubertal Boys: Summary of Eleven Cases and Recommendations for Case Management,” Pediatrics 27 (1961): 286–291).

American Psychological Association, Distinguished Scientific Award for the Applications of Psychology (1985) (“For [John Money’s] unparalleled contributions to theoretical analysis and clinical treatment in human sexuality. He originated the seminal concepts of gender identity and gender role, which form a cornerstone in all modern theories of sexuality.”).

Compare Henry Bracton, The Laws and Customs of England, 22 (Harvard Law School Library Bracton Online, 2003) (“Law is a general command, the decision of judicious men, the restraint of offences knowingly or unwittingly committed, the general agreement of the res publica. Justice proceeds from God, assuming that justice lies in the Creator… and thus jus and lex are synonymous.”) with HLS LGBTQ Alliance, “Joint LAMBDA-QTPOC Statement on Recent Hate Speech on Campus,” The Harvard Law Record, October 6, 2023 (“The antiquated and parochial belief in a so-called ‘naturally ordered society’ has long been used to justify and allow the deprivation of certain groups from access to meaningful human experiences and participation in public life.”).

Cf. Paul Matey, “Indispensably Obligatory”: Natural Law and the American Legal Tradition, 46 HARV. J.L. & PUB. POL’Y 967, 976 (“That is why human laws must have their root in the natural law and have as their end the common good. We are not wandering through a dark forest when interpretation requires us to turn to the ‘reason and spirit’ of our law. Because as Blackstone makes clear, and the Framers agreed, the ‘reason and spirit’—manifesting the lawmaker’s intentions through language—are the law.”).

See 2 Chronicles 33:1-9.

2 Chronicles 34:3-5 RSVCE.

Cf. Adrian Vermeule, “‘It Can’t Happen’; Or, the Poverty of Political Imagination,” Postliberal Order (November 19, 2021) (“... the radicals, the extremists, the idealists, the critics, the dissenters, the activists of social change, have in my lifetime been far more realistic, and simultaneously more imaginative, about the capacious and flexible limits of political and legal change.”).

O. John Rogge, The Rule of Law, 46 A.B.A. 981, 981 (1960) (“Insculpted in Stone over the portals of the main entrance of the Harvard Law School’s Langdell Hall are words which Edward Coke in his famous Sunday morning conference (1608) with James I of England quoted himself as saying, attributing them to Bracton, NON SUB HOMINE SED SUB DEO ET LEGE [not under man but under God and the law].”)

For those of us not in the in-crowd, the article could have supplied more context....

Well written. But I think you may be a bit off on Aquinas, what your describing is much more lie voluntarism, which Aquinas explicitly opposed

and re proceduralism and conservatives, I'm not so sure, in the 1970s and 1980s lower case "c" conservatives (e.g. Bork et al.) were just making it up as they went along until they and the special interest groups they were connected with did it so much successfully that it just became law and even in some senses a change to the sort of always there informal constitution